Le infermiere filippine che affrontarono Richard Speck e la donna che lo portò alla giustizia

Nota: Questo articolo tratta di un evento storico e può contenere temi delicati.

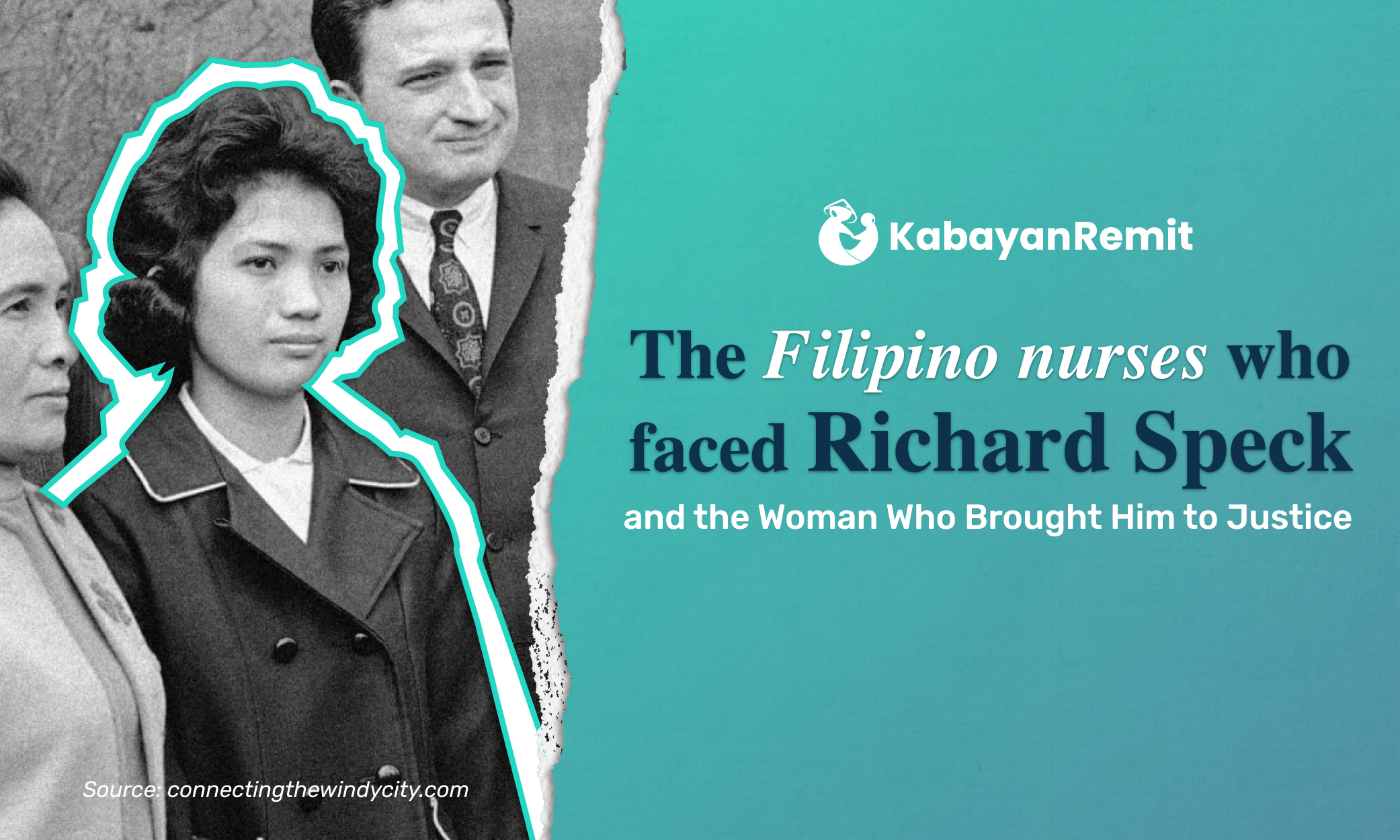

La mattina presto del 14 luglio 1966 a Chicago, IllinoisCorazon Amurao, 23 anni, è diventata l'unica sopravvissuta di Richard Speck, Il primo assassino di massa d'America. L'infermiera di scambio filippina è sopravvissuta strisciando e nascondendosi sotto un letto a due piani mentre Speck era distratto dalle altre vittime.

Alcune ore dopo, Amurao uscì dal suo nascondiglio e si rese conto che i suoi otto compagni di casa erano spariti.

Tra loro c'erano due infermiere filippine, Valentina Pasion e Merlita Gargullo. Loro e Amurao erano negli Stati Uniti solo da qualche settimana.

Anche Gloria Davy, Patricia Matusek, Nina Jo Schmale, Pamela Wilkening, Suzanne Farris e Mary Ann Jordan furono vittime di Speck quella notte. Erano tutte ventenni e avevano appena iniziato la loro carriera di infermiere.

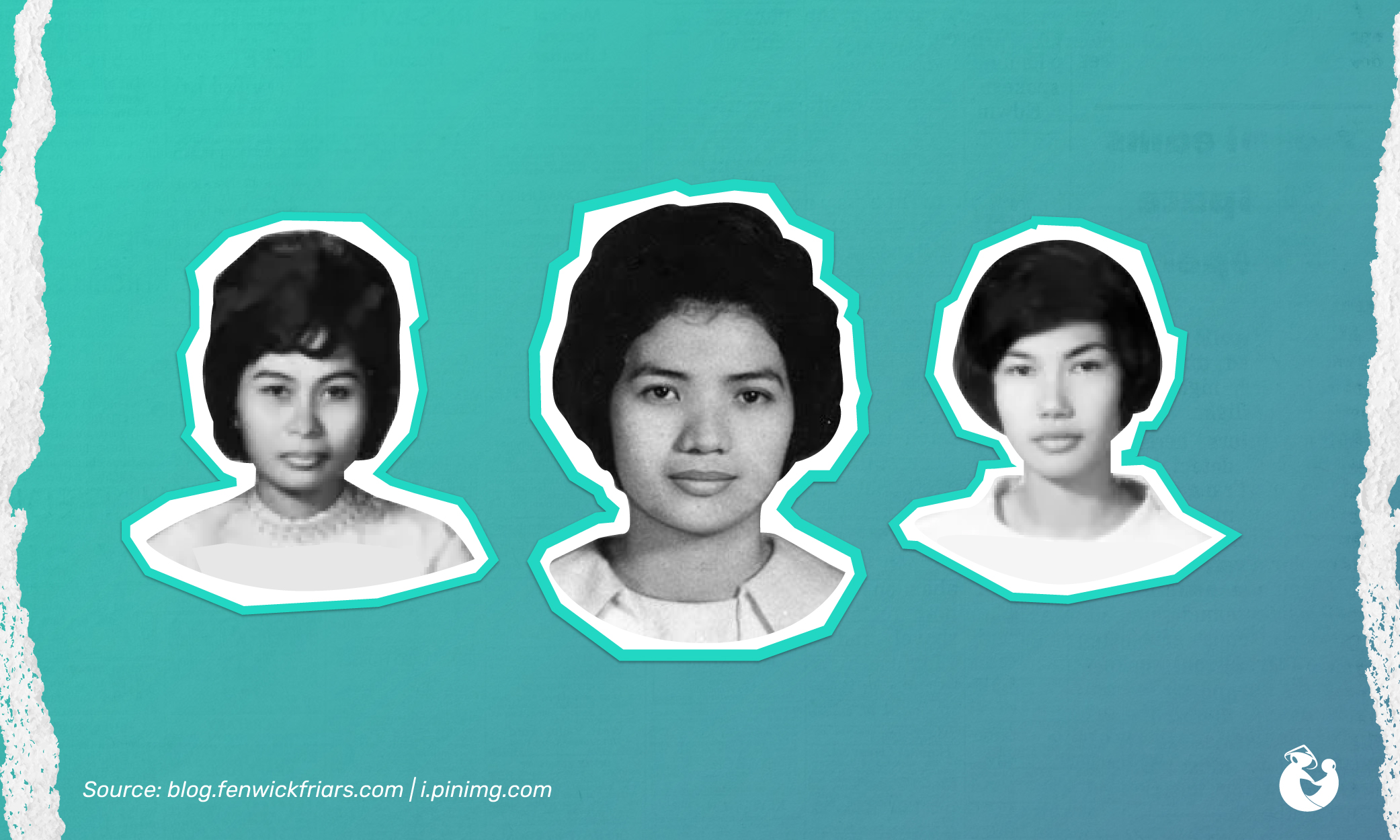

Le tre infermiere filippine del 2319 East 100th Street

Amurao, Pasion e Gargullo erano tre giovani Filippini che ha lavorato come scambiatore infermieraal South Chicago Community Hospital. Tutti e tre vivevano in quella che sarebbe poi diventata la scena del crimine: 2319 East 100th Via.

Amurao, alumna della Far Eastern University e nativa di San Luis, Batangas, era nota per la sua capacità di adattamento e la sua grazia sotto pressione. Queste doti le sarebbero tornate utili la notte del delitto e nei mesi precedenti. Speckl'arresto e la condanna.

Nelle Filippine, Pasion, 23 anni, si era laureata tra i primi 10 del suo corso all'Università Centrale di Manila. Prima del crimine, Pasion aveva scritto ai suoi genitori promettendo di inviare del denaro per sistemare la loro casa a Isabela.

Figlia di un medico di Mindoro, la 23enne Gargullo si è laureata all'Università di Arellano. Le sue colleghe infermiere ricordano la sua bella voce canora e le deliziose adobo e pancit avrebbe cucinato per loro.

L'omicidio di Pasion, Gargullo e dei loro compagni di stanza ha sconvolto il mondo per la sua insensatezza.

Spiegando perché ha commesso quello che è stato definito il crimine del secolo in America, Speck ha solo detto: "Non era la loro serata".

Ma la fortuna è stata dalla parte di uno infermiere lato. Un altro Filippino che sarebbe stato Speck's 10th vittima se non fosse tornata a casa quella sera.

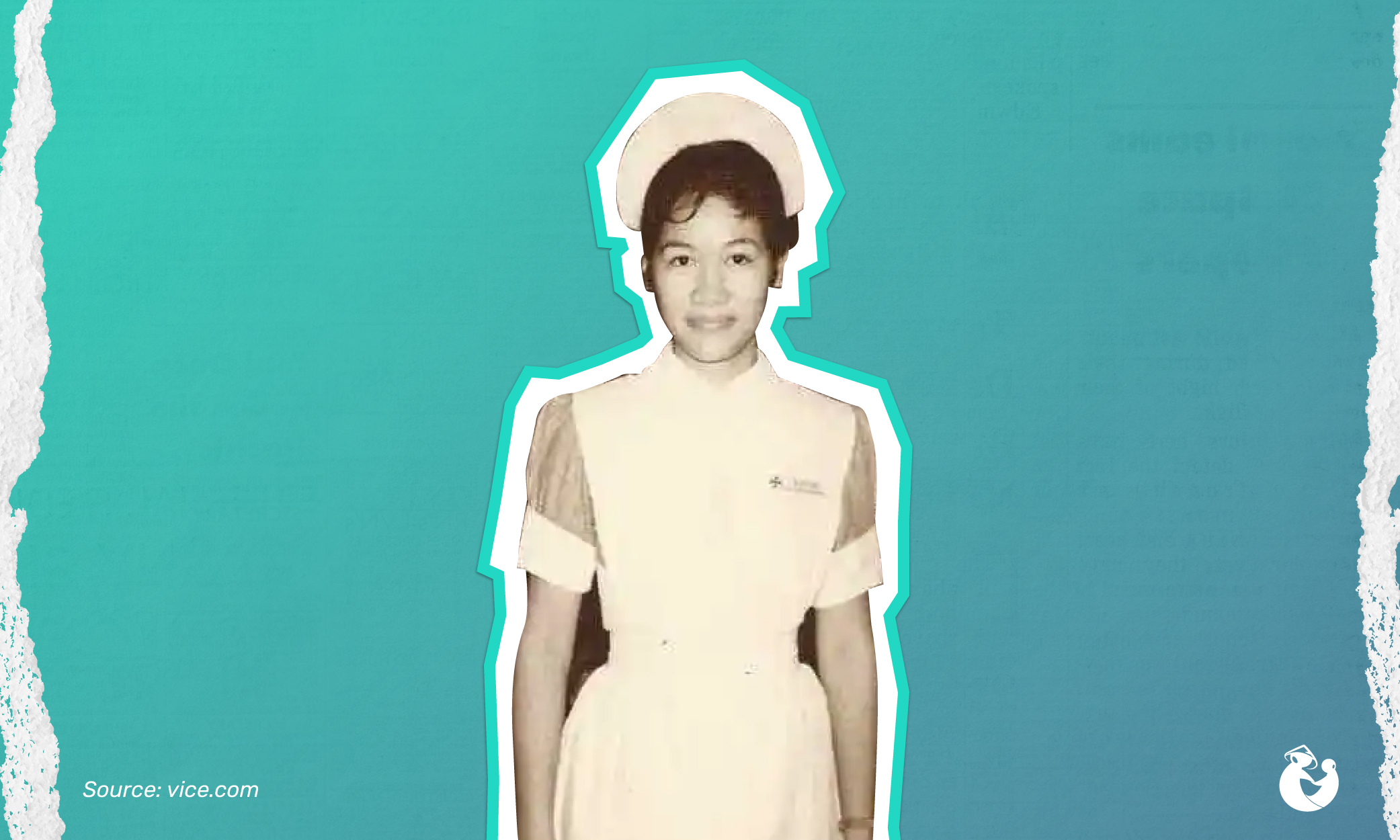

Luisa Silverio

Poche ore prima Speck arrivato, Filippino scambio infermiera Luisa Silverio e la sua collega e amica Pasion si stavano facendo le unghie a vicenda alla Townhouse 2319.

Mentre parlavano della nostalgia di casa, Pasion progettò di cucinare il pancit per cena e invitò Silverio a fermarsi per la notte.

Silverio è poi tornata al suo appartamento vicino per scrivere a casa e fare i bagagli per il pigiama party. Mentre si trovava lì, l'ospedale di comunità le telefonò per chiederle di fare un turno la mattina successiva.

Con il lavoro che ha cambiato i suoi piani, Silverio è tornata alla casa 2319 per ritirarsi personalmente dal pigiama party.

Suonò il campanello d'ingresso. Non risponde.

Provò a suonare il campanello sul retro. Silenzio.

Quando nessuno si affacciò alla porta, Silverio suonò un'ultima volta il campanello d'ingresso. Niente.

Pensando che non ci fosse nessuno in casa, Silverio tornò nel suo appartamento.

In documenti del tribunaleAmurao ricordava di aver sentito un campanello, di essere sceso al piano di sotto con Speck e un altro coinquilino a rispondere, e non vedendo nessuno alla porta. Probabilmente Silverio era andato sul retro a suonare il secondo campanello quando Speck ha aperto la porta d'ingresso.

Dopo il primo campanello, Speck ignorò i due squilli successivi, finché Silverio non rientrò in casa.

"[Ha] inavvertitamente corteggiato la morte per tre volte e ne è uscita indenne", ha scritto la nipote di Silverio Ysabel Vitangcol per Vice.

A differenza di Silverio, Mary Ann Jordan non fu altrettanto fortunata. Quella notte dormì nella casa 2319.

Incerta se parlare avrebbe influenzato la sua carriera di infermiera e il suo sogno di trasferirsi negli Stati UnitiSilverio non ha condiviso la sua storia con il pubblico per oltre 50 anni.

Anni dopo, ha detto che il crimine e la perdita dei suoi amici e colleghi hanno spezzato anche il suo cuore.

Silverio ha dichiarato a Vitangcol: "Sono rimasto traumatizzato. È stato devastante. Io e le mie colleghe infermiere non facevamo altro che piangere".

Questo non era ciò che lei, Pasion, Gargullo, Amurao e i loro colleghi Infermieri filippini che avevano immaginato per loro stesse quando hanno lasciato le Filippine per lavorare come infermiere negli Stati Uniti.

Infermiere filippine negli Stati Uniti

"Dopo che gli Stati Uniti hanno colonizzato le Filippine alla fine del XIX secolo, il Paese si è affidato agli operatori sanitari filippini per colmare le lacune di personale del sistema sanitario americano, soprattutto in tempi di crisi medica", ha scritto Paulina Cachero in un articolo per Tempo.

Con l'eccezione degli ospedali coloniali e missionari, all'inizio del periodo coloniale americano nelle Filippine c'erano poche strutture mediche in grado di curare i soldati americani affetti da malattie e infezioni.

Gli Stati Uniti hanno quindi istituito scuole e ospedali per produrre più personale sanitario nell'arcipelago.

Tra le Infermiera filippinal governo coloniale ha addestrato, alcuni selezionati si sono recati negli Stati Uniti per affinare le loro capacità, finendo per sostituire i loro capi americani nelle scuole e negli ospedali quando sono tornati nelle Filippine.

Per molti filippini dell'epoca, l'assistenza infermieristica rappresentava il percorso di carriera verso la rispettabilità e la stabilità finanziaria.

Poi, con la carenza di personale infermieristico dopo la seconda guerra mondiale, il programma di scambio di visitatori degli Stati Uniti ha aperto le porte a un maggior numero di persone. Infermiera filippinanel 1948. Il programma permetteva agli infermieri formati all'estero di fare esperienza e lavorare in America per due anni.

Negli anni '60 si è aperta una seconda porta per Infermiera filippinas.

La Legge sull'Immigrazione e la Nazionalità ha creato un percorso per i visitatori Infermiera filippinadi diventare residenti permanenti negli Stati Uniti in un momento in cui gli ospedali americani faticavano a curare i numerosi pazienti che usufruivano dell'assistenza sanitaria tramite Medicare e Medicaid.

Nel frattempo, il governo filippino degli anni Sessanta, guidato dall'allora presidente Ferdinand Marcos Sr., spingeva affinché i filippini lavorassero all'estero e inviassero denaro nelle Filippine come modo per sostenere l'economia nazionale.

In quel periodo Amurao, Pasion, Gargullo e Silverio entrarono negli Stati Uniti come infermiere di scambio.

Ed è in questo decennio che Amurao sarebbe diventato il testimone chiave che avrebbe messo Speck in prigione e rendere giustizia ai suoi amici.

In piedi contro Speck

"Forse mai nella storia della polizia di Chicago la chiave di un omicidio è stata più affidata all'esile filo della memoria di una ragazza di una notte di orrore", ha scritto Noble DeSalvi per Il Daily Calumet appena due giorni dopo il crimine.

La polizia doveva sperare che Amurao riuscisse a ricordare tutto di quella notte, nonostante avesse sopportato ciò che avrebbe potuto far crollare chiunque avesse un temperamento più debole.

Intorno alle 23 del 13 luglio 1966, proprio mentre stava per andare a dormire, Amurao sentì bussare alla porta della sua camera da letto. Aprendo la porta, vide Speck che brandiva una pistola e un coltello.

Amurao e la sua compagna di stanza sono poi corse nella stanza di un'altra amica e si sono nascoste in un armadio. Pochi minuti dopo, una compagna di casa le ha convinte a uscire dal nascondiglio, dicendo che Speck non avrebbe fatto loro del male.

L'ha fatto.

Quella notte morirono otto infermiere, ognuna scelta da Speck in un'unica stanza dove aveva raccolto tutte le sue vittime spaventate. Solo Amurao sopravvisse infilandosi sotto un letto a due piani, nonostante Speck le avesse legato mani e caviglie con strisce di lenzuola strappate.

Rimase nascosta per cinque ore, vedendo Speck prendere i suoi amici uno ad uno.

Alle 5:30 del giorno successivo, quasi tre ore dopo che Speck aveva lasciato la scena, Amurao si slegò e uscì dal suo nascondiglio.

Inorridita dalla vista dei suoi amici scomparsi, Amurao è salita sul cornicione di una finestra e ha gridato aiuto.

Appena un giorno dopo aver assistito al crimine, Amurao ha parlato per due ore con la polizia di Chicago. Ha fornito dettagli per un schizzo della polizia di Speck che ha fatto il giro dei media. Ha anche identificato Speck da un confronto fotografico.

Ma tra gli indizi più importanti che ha fornito alla polizia c'è il ricordo del tatuaggio "Born to Raise Hell" sul braccio di Speck.

La stampa ha pubblicato la storia.

Poco dopo, un medico curante Speck per autolesionismo ha notato il suddetto tatuaggio e ha chiamato la polizia.

E su 19 luglio, Amurao affrontato Speck nella sua stanza d'ospedale e ha confermato la sua identità alla polizia.

Meno di un anno dopo, si è ritirata dal banco dei testimoni e ha indicato Speck davanti a un giudice e a una giuria a Peoria, Illinois il 6 aprile 1967.

Disse, tenendo l'indice a pochi centimetri dal viso di Speck: "Questo è l'uomo".

Il il defunto William Martin, procuratore capo nella causa contro Speck, ha detto:

"La maggior parte dei testimoni diceva: 'È l'uomo con il vestito nero, ecc. o lo indicava dal banco dei testimoni. Cora - e questo fu motivo di stupore per tutti, per me più che per chiunque altro - aprì la porta, scese dal banco dei testimoni, attraversò l'aula, andò al tavolo dove era seduto Speck. Si avvicinò a lui e portò il dito a due centimetri dalla sua fronte, lo indicò e disse: "Questo è l'uomo". E per poco non scoppiò il pandemonio".

"È stato il momento più drammatico che abbia mai visto in un'aula di tribunale, prima o dopo", ha detto.

Nonostante il trauma, Amurao ha trascorso ore alla sbarra raccontando il crimine e affrontando l'esame incrociato.

Dodici giorni più tardi, la giuria ha stabilito che Speck colpevole di omicidio solo dopo 49 minuti delle deliberazioni.

Fu condannato a morte nel giugno 1967, ma fu nuovamente condannato a otto ergastoli consecutivi negli anni '70 a seguito di una sentenza della Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti. Trascorse il resto della sua vita in carcere e morì di infarto nel 1991.

Corazon Amurao ora

Dopo il processo, Amurao tornò nelle Filippine con un quarto della ricompensa di $10.000 per il suo ruolo nella condanna di Speck.

Ha avuto una breve esperienza nella politica locale, quando si è candidata a consigliere comunale a San Luis, Batangas sotto il Partito Liberale nel 1967.

Nel 1969, Amurao ha sposato Alberto Atienza nelle Filippine. La coppia si trasferì negli Stati Uniti negli anni '70.

Lì, Amurao ha mantenuto una vita privata e ha costruito una carriera come infermiera di terapia intensiva a Washington, D.C. fino al suo pensionamento nel 2013.

Mentre lavorava come infermiera, Amurao ha cresciuto due figli: Abigail, che ha intrapreso la stessa professione, e Christian, che è diventato commercialista.

Amurao è ora una nonna orgogliosa di sei nipoti, ma porta ancora le cicatrici di quella fatidica notte.

Il suo coraggio e la sua eredità

"Ha dimostrato l'indomabilità del suo spirito continuando il suo percorso come infermiera e dedicando la sua vita ad aiutare gli altri e a crescere una famiglia, ma una cosa del genere non si può mai togliere dalla propria vita", ha detto Martin a Rosemary Sobol della Chicago Tribune nel 2016, cinque decenni dopo il crimine.

Amurao ha detto qualcosa di simile in un'intervista del 1991 a ABC 7 Chicago, una delle sue uniche interviste dopo il delitto: "Dopo quella notte, ho sempre paura, sa. Non sono quel tipo di persona, perché sono sempre una persona felice. Ma dopo quella notte sembra che mi abbia tolto un po' di felicità".

A distanza di anni, Sobol ha riferito che Amurao ha ancora incubi su Speck che sta venendo a prenderla.

Ma Amurao ha mantenuto la sua fede.

Secondo Sobol, Amurao ha inviato un'e-mail all'ex procuratore Martin, dicendo: "Penso che ci sia qualcuno lassù che mi sta nascondendo [...]".Speck]. Dio è stato così gentile".

Era un'eco di ciò che aveva detto alla ABC 7 Chicago nel 1991: "Penso che [Dio] mi abbia risparmiato perché io possa fare più cose".

E altre cose che ha fatto.

Informazioni su Kabayan Remit

Kabayan Remit è un'applicazione per il trasferimento di denaro online che aiuta gli OFW a inviare denaro in modo sicuro a banche affidabili, portafogli elettronici e centri di rimesse in contanti nelle Filippine. È già disponibile nel Regno Unito e in Canada e presto lo sarà anche in Italia. Illinois, Florida e Arizona.

Per saperne di più sulle nostre funzioni e per provare il nostro calcolatore di tassi di cambio gratuito, fare clic su qui.